Ask a Planeteer: The Future of Water Resource Management

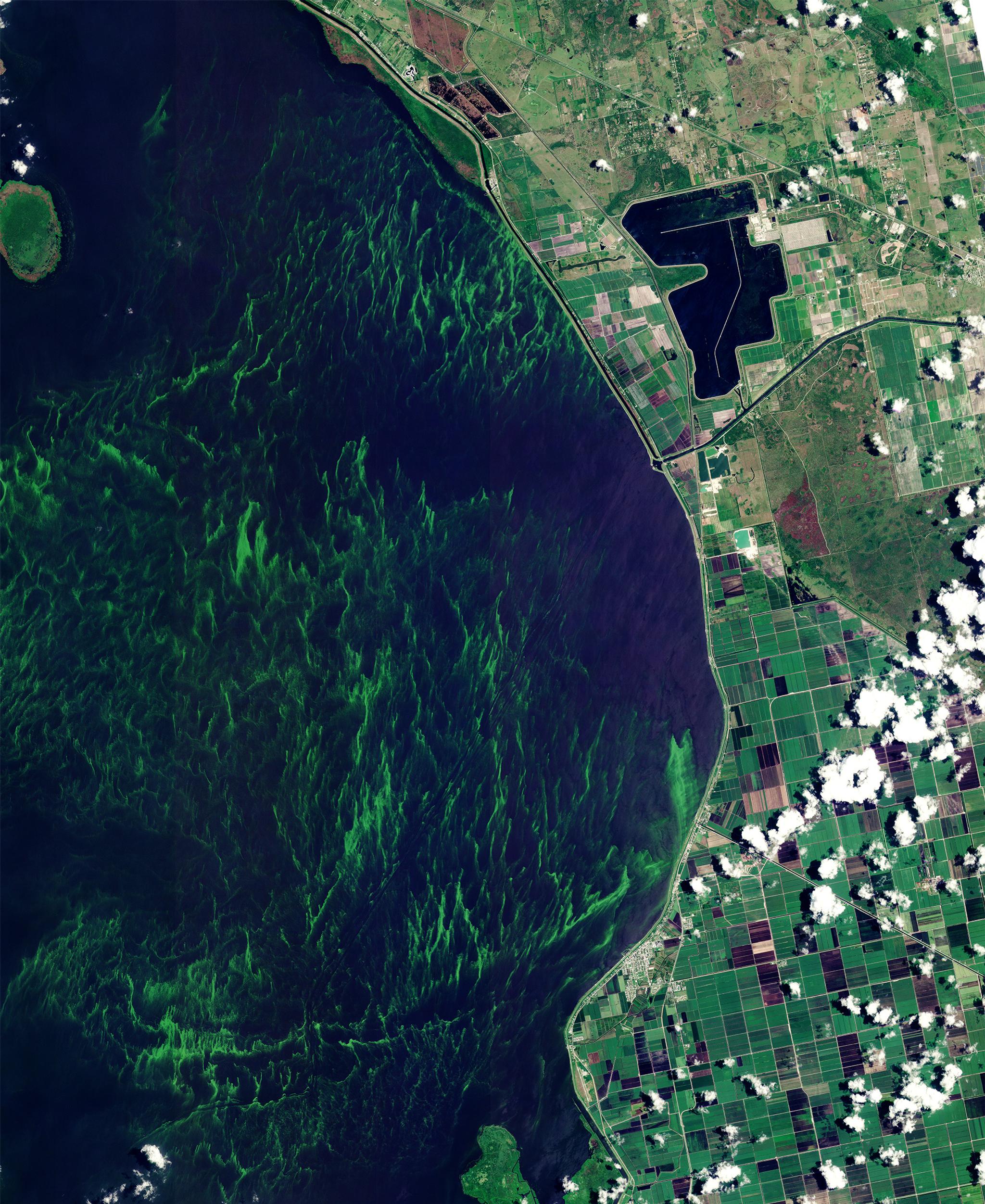

PlanetScope image of Lake Okeechobee, Florida, USA, captured June 12, 2023. © 2023 Planet Labs PBC. All Rights Reserved.

StoriesAt Planet, we’re fortunate to work alongside scientists who have deep subject matter expertise in remote sensing. We recently sat down with Chippie Kislik, whose PhD focused on the application of satellite imagery and drone technology in water resource management. Chippie works as a member of our pre-sales team, helping government customers around the world bring Planet data into their workflows.

Read on to learn about her path into water resource management. And if you’re interested in learning about how Planet data and tools help governments monitor water resources more effectively, download our new e-book, Transforming Water Resource Management with Planet.

Hi Chippie – thanks so much for sitting down with us today. Can you tell us a little about your background? What sparked your interest in water quality and how did it evolve into a PhD?

When I was really young, my grandparents would often take me to a lake in New York state to go swimming. Occasionally there were algal blooms. In the back of my mind, I was always wondering, “Is this okay?” As a teen I was really interested in environmental science. It continued as I entered UC Berkeley, where I also began learning GIS. That’s when I realized I loved mapping!

After college, I worked at the NASA DEVELOP program. We did a project focused on harmful algal blooms (HABs) in Lake Erie and used satellite imagery to see a lot of the water quality issues. That led me to a Fulbright in Ecuador, where I was able to study algal blooms around the Galápagos Islands. Eventually, I went back to UC Berkeley for my PhD to continue that type of research, but in a freshwater ecosystem.

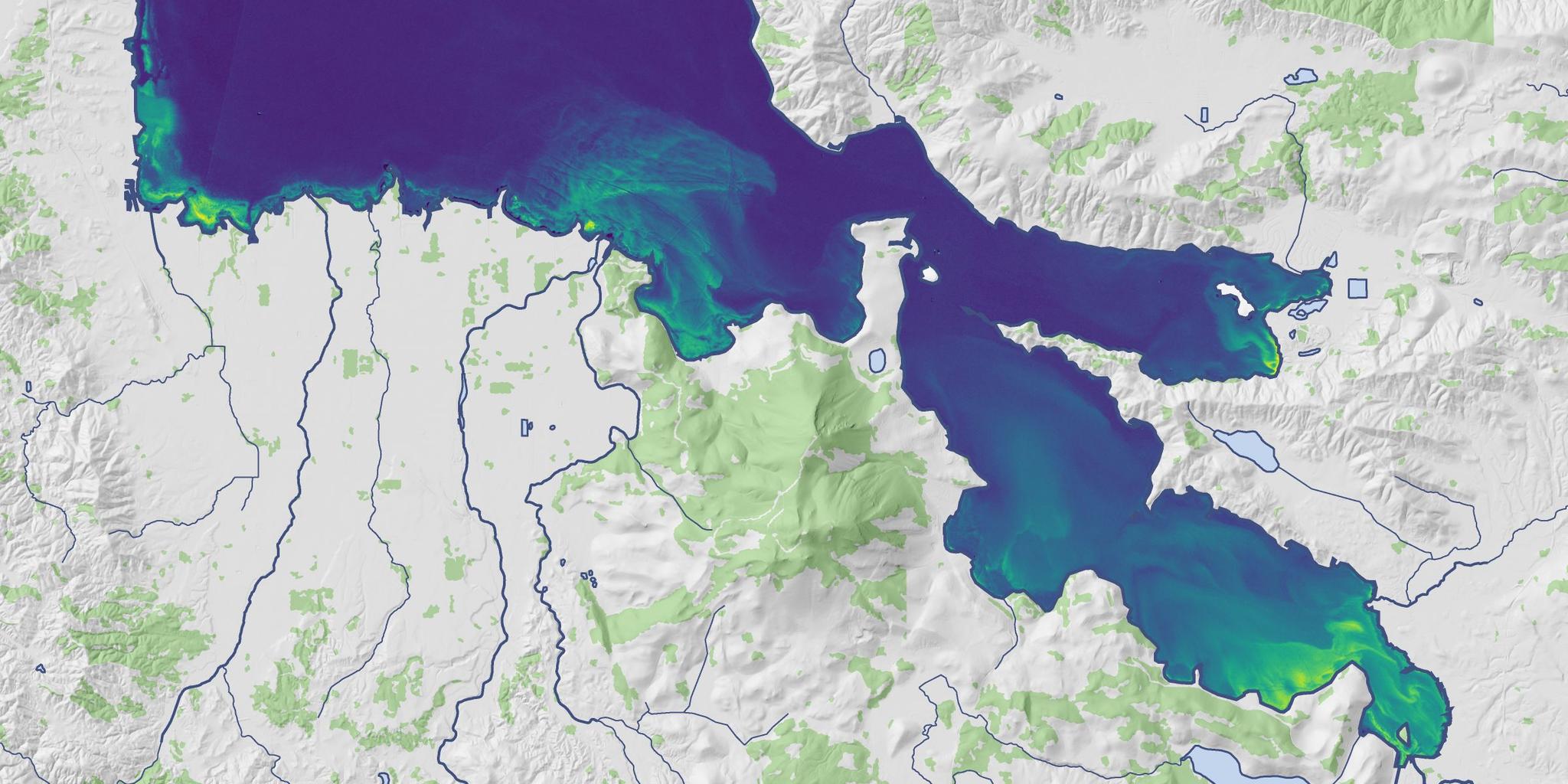

PlanetScope image of Lake Erie near Canada, captured February 20, 2024.

What types of water bodies did your PhD focus on?

It was mostly freshwater lakes, reservoirs, and rivers in California. Freshwater ecosystems are really interesting to me because they often have anthropogenic inputs from fertilizers or sewage effluent, or other sources we may be able to influence to reduce water quality issues.

I’m picturing you wading around a lagoon near a pipe with sewage effluent.

Yeah, I’ve done that. I was on a beach on San Cristóbal in the Galápagos. It had sewage effluent coming out of it. The locals knew that if you swam there too long, you’d get a rash.

But I heard you’ve also mapped all of the hot springs in California, which sounds a little more pleasant.

This is true! I did that in college. California has so many amazing hot springs. My mission is to soak in all of them eventually.

When and why did you start using Planet data in your PhD research?

I started using Planet data when I was looking at smaller lakes and reservoirs throughout California. The publicly-available datasets were a little too coarse to look at some of the smaller water bodies. Higher resolution was really helpful to look at specific areas of the shoreline where you might start seeing blooms and for finding better areas to monitor. It really helped monitor seasonal trends — and even rapid changes. Algal blooms change really quickly, even in just a few hours.

PlanetScope imagery, Clear Lake, California, USA, captured July 8, 2022.

What’s your day-to-day like as a pre-sales engineer at Planet?

A lot of my work is customer-facing. I really enjoy figuring out the best way to implement Planet data and tools in their workflows. We get requests for pretty much any type of use case you can imagine. These range from environmental use cases like water quality, wildfires, deforestation, forest carbon, and into things like real estate, to even … searching for aliens.

Sorry, what? Aliens?

We’ve had a couple of requests when people have seen unidentified objects. They wanted to see if our imagery could capture it. I haven’t been successful in my search thus far (but it doesn’t mean they’re not out there).

Interesting. So, getting back to water: what makes Planet data so unique? Why do governments use Planet data when they already have public satellite data, stream monitors and field sampling?

Governments use Planet data because it really brings a more complete view of watersheds. PlanetScope imagery has excellent spatial and temporal resolution. It complements Sentinel-2 data, and enhances it by allowing you to see more detail over specific locations where you might not have monitoring capabilities today. Many customers have said it helps them spend money more effectively. With better visibility, you can answer questions like, “When do we need boots on the ground? When is it less necessary to send people to the field?”

The 8 spectral bands are also important. Mainly, I’ve seen people use the red edge band, red, near-infrared, and sometimes the green and near-infrared to look at where water is and where it’s not. We have a yellow band that you can use for cyanobacteria assessments. All of those bands can be harmonized with Sentinel-2.

Planet data seamlessly integrates into our Planet Insights Platform (formerly known as Sentinel Hub) for time series analysis, which is really helpful for monitoring algal bloom dynamics. I love it because I can apply different water quality indices to my areas of interest instantly, and this platform is all on the cloud, so no need to download anything. This is great for assessing seasonal and interannual trends of both big and small water bodies pretty much anywhere in the world!

PlanetScope image of Maracaibo, Venezuela, captured June 22, 2023.

What kind of water quality indicators can we help measure?

Algal blooms and turbidity are really big ones. We can look at turbidity with the red band. We can look at chlorophyll-a as a proxy for algal biomass using bands such as the red and red-edge. You can also use Planet data to monitor sedimentation, like when there’s a lot of silt pouring out into a water body.

PlanetScope image of Sambas, Kalimantan, Indonesia, captured May 18, 2023.

You can see most things down to about a meter of the water column with high-resolution satellite imagery, depending on water clarity. If you’re in the Caribbean, you can see much farther down. Some customers have used Planet data to look at the quality of corals in different habitats. Others have worked with our partners to measure water depth, also known as bathymetry. We’ve even had researchers measure streamflow velocity with our SkySat videos.

It’s also really helpful to have the short-wave infrared band with our hyperspectral mission to look at water quality issues such as oil spills and suspended sediments. This mission has 30x30 m spatial resolution, but if you’re looking at a really big water body, or even coastal areas, that’s very helpful.

PlanetScope image of Bermuda captured April 15, 2022.

Of all the water-related use cases we have today, what is the most interesting one for you?

I’m usually biased toward water quality because algal blooms are becoming more common in many parts of the world. But for the purposes of shaking it up — whale spotting! Some people have used our SkySat imagery to spot whales and seals off the coast of New Zealand and Alaska.

_________________________________________________________________________________

Ready to learn more about how Planet data and tools can help your agency? Download our e-book, Transforming Water Resource Management with Planet.

Ready to Get Started

Connect with a member of our Sales team. We'll help you find the right products and pricing for your needs.