From ClimateWeek to COP27, COP15, and Beyond: Notes on the Road Ahead

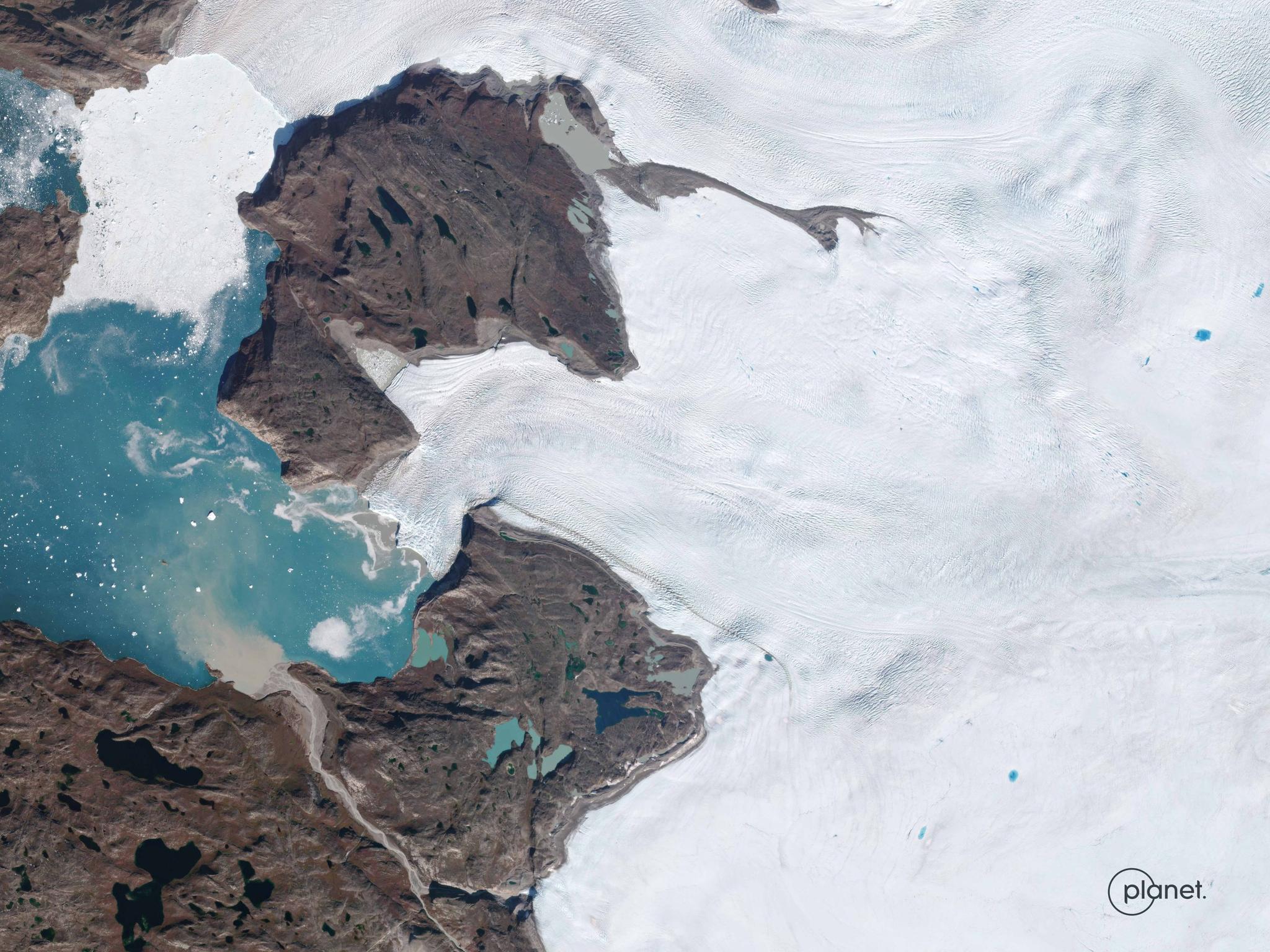

Planet image of a Greenland ice melt taken September 4, 2022. © 2022, Planet Labs PBC. All Rights Reserved.

StoriesOpinion

World leaders, CEOs, climate advocates, scientists and sustainable development specialists from around the world converged on New York City last week, for the annual, concurrent rituals of the United Nations General Assembly and ClimateWeek. After a several years’-long lull, things were back with a bang - with more people, more meetings, more energy, and more urgency.

Across dozens of meetings, key elements in an invigorated climate and sustainable development agenda reappeared as consistent topics of conversation – and they are sure to be taken up in other critical global meetings later this year.

Here are my four key takeaways:

- U.S. Domestic Climate Policy Gets Real

The recently-passed Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) is such a game-changer for domestic climate action that experts at ClimateWeek often referred to it, reflexively, as the Emissions Reduction Act. Nearly $370b in tax credits, clean energy incentives, and investments in green innovation are intended to dramatically accelerate domestic decarbonization in sectors from energy to manufacturing. It aligns U.S. rhetoric and financing and catapults the U.S. back into a position of global climate leadership.

The transition envisioned in the IRA is awesome in the literal sense: it represents one of the largest prospective transformations of the physical basis of American society since the mid-20th century, when the U.S. built things like the Hoover Dam and the Interstate Highway System.

For example, to fully transition the U.S. to a carbon free economy by 2050, experts at Bloomberg and Princeton estimate that the US will have to build enough solar and wind farms to fill an area roughly five times the size of South Dakota. The land-use and environmental implications of all of that renewable energy infrastructure will be profound and have to be carefully thought through. That’s a major reason why Planet, Microsoft and The Nature Conservancy announced an important new initiative called Global Renewables Watch, a first-of-its-kind living atlas that will map and measure every utility-scale solar and wind installation on Earth using artificial intelligence and satellite imagery. This new system is intended to allow users to evaluate progress on renewables, and track their land-use impacts over time. It is estimated to be fully available in 2023.

The decarbonization that the landmark climate bill promises is intended to have countless impacts on businesses, as well. For many, it has the potential to change their cost structure, accelerate their Net Zero ambitions, remake their supply chains and create new growth opportunities. It very well could move climate, sustainability and ESG-linked efforts even more directly into the boardroom. That, in turn, should drive a much greater appetite for climate-linked data. In the years to come, organizations will need to measure both the climate risk to their physical assets, as well as their assets’ risks to the climate. In numerous sessions, speakers at ClimateWeek addressed the need for clear data standards for measuring these risks. They also noted that one of the surest paths to a low-carbon future is replacing atoms with bits wherever possible - linking the sustainability transition to digital transformation.

- The Global Focus Shifts to Adaptation

Meanwhile, on the global front, a complementary agenda is coming into focus. COP27, which will be held in Egypt this November, will be different in several key respects from the Glasgow edition that preceded it in 2021.

First and foremost, there will be a much stronger focus on climate adaptation,rather than solely on mitigation.

Today, 90% of climate finance is focused on mitigation - stopping the sources of climate change at their origin, rather than adapting to their effects. This makes a certain sense: if you don’t plug emissions at the source, climate change becomes ever-more entrenched and impactful with every passing year – eventually, catastrophically so. Yet focusing solely on mitigation overlooks the glaring fact that most of the worst impacts will not be felt by the people who caused climate change, but by those who are on the receiving end of it, and who are often least-well-resourced to adapt. (See this remarkable set of global maps, created by Prof. Jason Hickel, which illuminates the countries responsible for climate change, and those who will be most affected. They are nearly-perfect mirror images.)

There is an obvious and essential social justice dimension to this, and the Egyptian convenors of COP27 have promised to put adaptation in all its forms - including financing, technology and policy – high on the agenda. Doing so is essential, not only for fostering a just transition, but for contending with the solemnly-whispered concern that the world is still nowhere near the path required to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

This will also be the first African COP in several years, and Egypt has promised to champion African interests, which perfectly encapsulates the issues raised above. According to the African Development Bank, Africa has received less than 5.5% of global climate financing, despite the fact that it has contributed minimally to global emissions and is disproportionately exposed to climate risks. Expect strong demands for (already-made, but unfulfilled) commitments of climate financing and assistance, as well as payments for climate “loss and damage” to predominate at COP27.

But climate adaptation isn’t just a national or social justice issue, it’s also (again) a global business concern, and like all such concerns, it contains elements of both downside risk and upside opportunity. There are leading businesses who will likely sink under the weight of their climate exposure, and others who will decouple and float. In several private meetings, corporate leaders have started to cohere around an adaptation agenda for business, and you should expect to hear more around this at COP27.

- The Ukraine Effect

The Russian invasion of Ukraine complicates the global climate agenda significantly, and in ways that are not easily summarized. The war exerted a dark, distorting force on conversations at UNGA and ClimateWeek this year: it was clear the conflict could either delay or galvanize climate transition – and will likely do both, in different ways and over different time spans.

In the near-term, the conflict is exerting negative impacts on climate emissions. For example, in June, Germany announced plans to restart coal-fired powerplants, in an effort to save its reserves of natural gas. The energy crisis caused by the conflict is causing a ‘coal rush’ around the world, to mine the fuel for Europeans to burn this winter. The price of thermal coal is expected to double, leading to production booms in mining towns in countries as far away as Tanzania and Botswana.

But, in roughly the same time period, Germany also went from supporting a second gas pipeline from Russia to scrapping it and announcing a 220 billion euro investment to accelerate the adoption of renewable energy – part of a long-term effort to decouple itself from its reliance on Russian hydrocarbons. Meanwhile, in nearby, traditionally coal-loving Poland, citizens are installing solar panels to do the same. As a consequence, many policy experts think the Ukraine conflict could be, as one UN colleague put it, “a short term negative, long-term positive” driver of the climate agenda.

The knock-on effects of the conflict also intersect with other climate-vulnerable systems, such as global food security. Ukraine is a global bread-basket, and interruption of its delivery of key staple crops, and the concurrent loss of Russian fertilizer, are likely to lead to serious disruptions next year. This is a disruption on top of a disruption: global food supply chains had already been convulsed by the COVID pandemic starting in 2020; subsequent efforts to combat the economic impact of the pandemic had the unintended effect of driving up commodity prices, putting what food was available further out of reach. The conflict has moved the global food system into great precarity - a climate-exacerbated drought or other natural disaster could become even more catastrophic for those affected.

The economic effects of the war are also likely to have a significant impact on the climate agenda. With security concerns spurring likely increases in military and defense spending, competing climate commitments could be significantly delayed or diminished. Experts estimate that rebuilding Ukraine after the conflict ends could cost $350 billion, more than half of current global investments in climate finance.

The invasion is also prompting a rethink about how to deliver the global climate agenda, and multilateral cooperation more generally, in a less-globalized and more fractious world. At one meeting on maritime security, for example, it was noted that the Arctic Council, a body composed of the eight countries of the high north – Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Russia and the United States – had effectively shut down in the wake of the conflict. In June 2022, seven of its eight members agreed to resume limited work – without Russia. In similar ways, the conflict is quietly cleaving numerous, climate-relevant coalitions, and reshaping assumptions about the global climate-security nexus.

- Toward a Global Deal for Nature

Finally, there was a lot of discussion at ClimateWeek and UNGA about the “other” COP - COP15, which is convening in December in Montreal. This is the Biodiversity COP, which will convene governments, NGOs, scientific organizations, companies and Indigenous peoples’ representatives from around the world to agree to a new set of goals for nature over the next decade - what are collectively the Convention on Biological Diversity (or “CBD”) post-2020 targets. Finalizing these targets is akin to establishing a “Paris Climate Agreement”-like framework for nature - and moves the concept of a “global deal for nature” forward. During ClimateWeek, we heard genuine interest from senior corporate and finance leaders in standardizing natural capital and biodiversity measurements, and doing so in a way that is informed by earlier attempts to bring carbon onto the balance sheet. As with carbon, technology can help standardize and scale these efforts. Tools like Planet’s planned hyperspectral satellites, called Tanagers, when operational, could play an important role in helping us measure biodiversity both in the places where it’s most at risk, and globally. Watch this space!

Ready to Get Started

Connect with a member of our Sales team. We'll help you find the right products and pricing for your needs